A rare disease is defined by the European Union as a condition that affects fewer than 1 in 2,000 people within the general population. There could be as many as 7,000 rare diseases. Despite having a low incidence, the total number of Americans living with a rare disease is estimated at between 25-30 million. These figures highlight that while individual diseases may be rare, the total number of people with a rare disease is large, a fact that is often misunderstood by those unfamiliar with the rare disease community.

Cyagen assists in the research of rare diseases and provides various mouse/rat models, including the SYNGAP1-related rodent animal models. This article focuses on the gene SYNGAP1 and rare disease MRD5, aiming to help interested researchers continue to build on scientific literature and knowledge.

Overview of SYNGAP1 Gene

SYNGAP1 (Synaptic Ras GTPase Activating Protein 1) is a Protein Coding gene. The SYNGAP1 gene is located on Chromosome 6 and is responsible for producing the SynGAP protein. This protein acts as a regulator in the synapses - where neurons communicate with each other. A variant of the SYNGAP1 gene leads to the gene not producing enough SynGAP protein. Without the right amount of SynGAP protein we see an increase in excitability in the synapses making it difficult for neurons to communicate effectively. This leads to many of the neurological issues seen in patients with SYNGAP1 mutation.

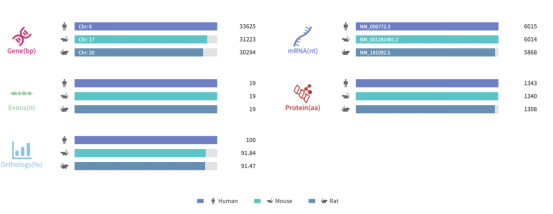

Figure 1. Gene information and sequence homology alignment of SYNGAP1

Source: Rare Diseases Data Center (RDDC)

Rare Diseases Associated with the SYNGAP1 Gene

Autosomal Dominant Non-Syndromic Intellectual Disability 5 (MRD5)

MRD5 (Mental Retardation, autosomal Dominant 5) is classified as a Rare non-syndromic intellectual disability. MRD5 is a condition caused by mutations in the SYNGAP1 gene that primarily affects the central nervous system. It is characterized by moderate to severe intellectual disability that is usually apparent in the first few years of life. Some affected people may also experience seizures and/or autism spectrum disorder. Almost all reported cases are due to de novo mutations; however, the condition can be passed down to future generations in an autosomal dominant manner. Treatment is based on the signs and symptoms present in each person.[1][2][3]

Loss-of-function mutations causing haploinsufficiency of the SYNGAP1 gene (and likely damaging the development of the forebrain glutamatergic neurons) are causative of the disorder. Most mutations are protein truncating (nonsense, frameshifting, splice mutations), although a minority of missense mutations has also been reported. Mutations reported thus far include the following:

One whole gene deletion has also been mentioned.[9] In fact, MRD5 may clinically overlap with 6p21.3 microdeletions (which causes the deletion of several genes including SYNGAP1), confirming that gene loss may also be expected as the cause of haploinsufficiency. Even patients with deletions that include SYNGAP1 and several other genes may show autism spectrum disorders [10] .

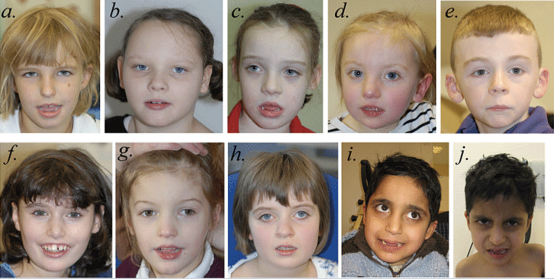

Figure. 1 Faces of individuals with SYNGAP1 haploinsufficiency. Facial photographs of Patient 1 at 7 years, 3 months (a); Patient 2 at 8 years,

2 months (b); Patient 3 at 7 years, 9 months (c); Patient 4 at 3 years, 2 months (d); Patient 5 at 8 years, 4 months (e); Patient 6 at 12 years, 10 months (f); Patient 7 at 5 years, 7 months (g); Patient 8 at 8 years, 7 months (h); and Patients 9 and 10 at 8 years, 3 months (i and j). The most common shared facial characteristics are almond-shaped palpebral fissures, which slant downwards slightly. With the exception of Patient 5 (e), the others have a mildly myopathic appearance, with an open mouth and relatively full lower lip. Patients 1 (a), 3 (c), 4 (d), 6 (f), 7 (g) and 9 (i) and 10 (j) have relatively long noses; Patients 2 (b), 4 (d), 5 (e), 6 (f), 7 (g) and 8 (h) have relatively long

ears with protuberant lobes. Patients 1 (a), 6 (f) and 9 (i) and 10 (j) were thought to have relatively deep-set eyes and Patient 8 (h) has a degree of ptosis. Patient 6 (f) has a missing central incisor due to trauma. We do not believe that Patient 7 (g), the only whole gene deletion patient in this series, differs significantly in appearance from the others.[9]

According to the data in the Orphanet database, there are currently no clinical trials for MRD5, and 26 research projects are underway.

Source: Orphanet [11]

Other Related Diseases

Most Seen Symptoms of SYNGAP1 Gene Mutations

What Can Cyagen Do?

Over the past year, Cyagen has focused on developing educational resources and initiatives to assist the rare disease research community. To help inform our R&D of precise animal models for rare disease studies, we initiated a Rare Disease Model Collaboration Program in the first quarter of 2021. With this program, we aim to build a community of rare disease researchers with ideas for the next generation of animal models needed to advance their field of study.

1. Berryer MH, Hamdan FF, Klitten LL, Møller RS, Carmant L, Schwartzentruber J, Patry L, Dobrzeniecka S, Rochefort D, Neugnot-Cerioli M, Lacaille JC, Niu Z, Eng CM, Yang Y, Palardy S, Belhumeur C, Rouleau GA, Tommerup N, Immken L, Beauchamp MH, Patel GS, Majewski J, Tarnopolsky MA, Scheffzek K, Hjalgrim H, Michaud JL, Di Cristo G. Mutations in SYNGAP1 cause intellectual disability, autism, and a specific form of epilepsy by inducing haploinsufficiency. Hum Mutat. 2013 Feb;34(2):385-94. doi: 10.1002/humu.22248. Epub 2012 Dec 12. PMID: 23161826.

2. Hamdan FF, Daoud H, Piton A, Gauthier J, Dobrzeniecka S, Krebs MO, Joober R, Lacaille JC, Nadeau A, Milunsky JM, Wang Z, Carmant L, Mottron L, Beauchamp MH, Rouleau GA, Michaud JL. De novo SYNGAP1 mutations in nonsyndromic intellectual disability and autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2011 May 1;69(9):898-901. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.015. Epub 2011 Jan 15. PMID: 21237447.

3. Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Spiegelman D, Noreau A, Yang Y, Pellerin S, Dobrzeniecka S, Côté M, Perreau-Linck E, Carmant L, D'Anjou G, Fombonne E, Addington AM, Rapoport JL, Delisi LE, Krebs MO, Mouaffak F, Joober R, Mottron L, Drapeau P, Marineau C, Lafrenière RG, Lacaille JC, Rouleau GA, Michaud JL; Synapse to Disease Group. Mutations in SYNGAP1 in autosomal nonsyndromic mental retardation. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 5;360(6):599-605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805392. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 29;361(18):1814. Perreault-Linck, Elizabeth [corrected to Perreau-Linck, Elizabeth]. PMID: 19196676; PMCID: PMC2925262.

4. Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Araki Y, Lin DT, Yoshizawa Y, Higashi K, Park AR, Spiegelman D, Dobrzeniecka S, Piton A, Tomitori H, Daoud H, Massicotte C, Henrion E, Diallo O; S2D Group, Shekarabi M, Marineau C, Shevell M, Maranda B, Mitchell G, Nadeau A, D'Anjou G, Vanasse M, Srour M, Lafrenière RG, Drapeau P, Lacaille JC, Kim E, Lee JR, Igarashi K, Huganir RL, Rouleau GA, Michaud JL. Excess of de novo deleterious mutations in genes associated with glutamatergic systems in nonsyndromic intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Mar 11;88(3):306-16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.001. Epub 2011 Mar 3. Erratum in: Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Apr 8;88(4):516. PMID: 21376300; PMCID: PMC3059427.

5. Berryer MH, Hamdan FF, Klitten LL, Møller RS, Carmant L, Schwartzentruber J, Patry L, Dobrzeniecka S, Rochefort D, Neugnot-Cerioli M, Lacaille JC, Niu Z, Eng CM, Yang Y, Palardy S, Belhumeur C, Rouleau GA, Tommerup N, Immken L, Beauchamp MH, Patel GS, Majewski J, Tarnopolsky MA, Scheffzek K, Hjalgrim H, Michaud JL, Di Cristo G. Mutations in SYNGAP1 cause intellectual disability, autism, and a specific form of epilepsy by inducing haploinsufficiency. Hum Mutat. 2013 Feb;34(2):385-94. doi: 10.1002/humu.22248. Epub 2012 Dec 12. PMID: 23161826.

6. Volk A, Conboy E, Wical B, Patterson M, Kirmani S. Whole-Exome Sequencing in the Clinic: Lessons from Six Consecutive Cases from the Clinician's Perspective. Mol Syndromol. 2015 Feb;6(1):23-31. doi: 10.1159/000371598. Epub 2015 Feb 3. PMID: 25852444; PMCID: PMC4369115.

7. Carvill GL, Heavin SB, Yendle SC, McMahon JM, O'Roak BJ, Cook J, Khan A, Dorschner MO, Weaver M, Calvert S, Malone S, Wallace G, Stanley T, Bye AM, Bleasel A, Howell KB, Kivity S, Mackay MT, Rodriguez-Casero V, Webster R, Korczyn A, Afawi Z, Zelnick N, Lerman-Sagie T, Lev D, Møller RS, Gill D, Andrade DM, Freeman JL, Sadleir LG, Shendure J, Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE, Mefford HC. Targeted resequencing in epileptic encephalopathies identifies de novo mutations in CHD2 and SYNGAP1. Nat Genet. 2013 Jul;45(7):825-30. doi: 10.1038/ng.2646. Epub 2013 May 26. PMID: 23708187; PMCID: PMC3704157.

8. von Stülpnagel C, Funke C, Haberl C, Hörtnagel K, Jüngling J, Weber YG, Staudt M, Kluger G. SYNGAP1 Mutation in Focal and Generalized Epilepsy: A Literature Overview and A Case Report with Special Aspects of the EEG. Neuropediatrics. 2015 Aug;46(4):287-91. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1554098. Epub 2015 Jun 25. PMID: 26110312.

9. Parker MJ, Fryer AE, Shears DJ, Lachlan KL, McKee SA, Magee AC, Mohammed S, Vasudevan PC, Park SM, Benoit V, Lederer D, Maystadt I, Study D, FitzPatrick DR. De novo, heterozygous, loss-of-function mutations in SYNGAP1 cause a syndromic form of intellectual disability. Am J Med Genet A. 2015 Oct;167A(10):2231-7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37189. Epub 2015 Jun 15. PMID: 26079862; PMCID: PMC4744742.

10. Cook EH Jr. De novo autosomal dominant mutation in SYNGAP1. Autism Res. 2011 Apr;4(2):155-6. doi: 10.1002/aur.198. PMID: 21480541.

11. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=EN&Expert=101685

We will respond to you in 1-2 business days.